This is the most difficult rule to follow because it requires us to know which problem is our most pressing. Unless we find ourselves in a burning building, sinking car or trying to board a plane — I almost typed the name of a crazy, chaotic airport like Newark or LAX, but then realized it didn’t matter: negotiating every airport has become a nightmare — the problem in front of us tends not to be immediately apparent.

I need a raise. I need a new job. My co-worker with the lisp and the grandchildren is driving me crazy. My favorite yoga instructor has moved on. I really am trying to be gluten free. My children can’t tear their eyes away from the iPads. Now they are zombies, except when they are playing soccer thirty hours a week. Did David Beckham play this much soccer in his heyday? More importantly, did his mother drive him to all those practices, scrimmages, games, clinics and photo days? I don’t think so. My mother is going to start drinking again when she reads the memoir I’m thinking about writing. That mole on the back of my knee shaped like Australia looks really weird. Do we really have to do Thanksgiving with your parents? Is no one going to step up and make Miley put her tongue back in her mouth?

First world problems, you may say, but problems nevertheless.

Here in Karbohemia we are thrilled to let you in on a secret. We have found the primary problem, a huge and pressing problem that is literally right in front of us, an immediate problem that we can all solve this very second and make our lives measurably better. (It is even based in science.)

Recently I was without my cell for a few days, during which I experienced the sort of radical freedom I used to feel growing up when our telephone hung dumbly on the kitchen wall. I never knew it was radical freedom and could never imagine a time when this would be the norm:

Before I went seventy-two hours without a phone I was the worst offender. You’d think I was awaiting word of a liver transplant, so ardently did I consult my phone. I felt anxious all the time, and I didn’t know why. It’s crazy and unhappy-making, this smart phone obsession.

But not for the reasons you may think.

Forget for a moment the addictive siren call of the internet, and how living with our phones glued to our palms is ruining our ability to focus, enjoy being in the moment, think deeply, or at all, or spend time with another human being. Here in Karbohemia we are more concerned with how our phone-checking posture is turning us into feeling as if we are sad sack losers.

Dr. Ann Cuddy, (whom I feel inordinately close to because I’m determined to believe she must be related to Dr. Lisa Cuddy) is a social scientist at Harvard and an expert on body language and non-verbal communication. We all know that our body language affects how others view us, but Cuddy and her research associates have discovered that how we hold bodies also affects how we view ourselves. And it’s not just positive thinking or manifesting whatnot, there’s biochemical evidence. You can watch her mind-blowing, posture-improving TED talk here, and it’s worth every one of its 21 minutes.

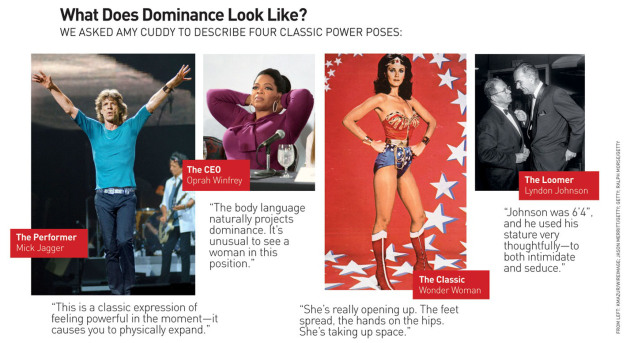

It’s all about what Cuddy calls the power pose, a gesture of confidence, assertiveness, optimism and joy that all humans naturally display. All primates naturally exhibit power poses; even people who’ve lived without sight from birth adopt certain body positions when they feel they’ve triumphed — chest out, chin up, arms in the air.

Michael Phelps and his teammate at the 2009 Beijing Olympics, super power posing. The official in the blue jacket, not so much.

Cuddy found that these poses not only display a sense of power to others, but also make us feel more powerful. It’s not unlike the study that contends if you smile, you begin to feel happier.

The crazy part is this: she performed several experiments in which her subjects’ saliva was tested both before and after they adopted a power pose, and found their hormone levels adjusted after a scant two minutes in one of these poses:

Holding a power pose caused the subjects’ testosterone levels to go up and cortisol levels to go down. This makes us feel that all is right with our world. Testosterone causes us to feel confident and assertive (not just compelled to make war and scratch our balls). Cortisol, the so-called stress hormone, is your best friend when you’re running for your life, but destructive the rest of the time, decreasing bone formation, burning out neural pathways, suppressing the immune system, and sharing partial responsibility for the formation of evil belly fat.

You’ve got to know what comes next. There are also poses — what Cuddy diplomatically refers to as low power poses — that have the opposite effect on us. After two minutes of sitting slumped with our legs and arms crossed, testosterone plummets and cortisol spikes. As a result we feel stressed, powerless, hopeless and unhappy.

Cuddy conducted another experiment. In this one, her subjects were interviewed for a job. Half of the group power posed for two minutes before their interviews and half did this:

The outcome was startling. The subjects who power posed for two minutes before their interview — remember, it alters your hormone levels for twenty minutes — were recommended for hire. How many of the subjects who spent their two minutes in low power poses were recommended for hire? None.

So that chick on the right checking her phone? Striking the classic low power pose. Rounded shoulders, sagging middle, crossed legs, consumed with life on the little screen.

It would be one thing if we checked our phones once in a while, but we’re pretty much always hunched over our screens. People who study such things claim it’s as much as 150 times a day. I’ll do the liberal arts major math for you: Let’s say we only check our phones 100 times a day (easier for me to do in my head, and also makes us appear less pathetically addicted), and only half of those checks are over two minutes long. (Most of the time we’re doing just that — checking — and it takes ten seconds, but if we’re tweeting, posting or writing an email, it may be as long as ten minutes). Fifty times twenty (the number of minutes your hormone level is affected by your pose) equals one thousand minutes of high cortisol/low testosterone, or about 16 hours and 40 minutes of feeling listless, stressed and unhappy. If you log in a solid eight hours sleep per night as I do, that’s every waking moment.

I’m not a Luddite (says everyone who rants about digital self-imposed slavery). I know smart phones aren’t going anywhere, but do yourself a favor and spend a few days checking it maybe once or twice a day, and see what happens. We in Karbohemia, feeling a flush of optimism and good will, have found that it does make a difference.

Sources:

People on phones/www.siliconangle.com; Michael Phelps/www.creativecreativity.typepad.com; “What Does Dominance Look Like?/www.smalltalkbigresults.com/Leigh Buchanan, Inc. Magazine; Low Power Pose/Ann Cuddy Ted Talk; Julia Child on “The French Chef,”/Paul Child/www.npr.org.

I really love this. For so many reasons. (One being now I know what to do before my next job interview!)

I am actually kind of famous for forgetting my phone. (Like all the time.) And when I don’t have it I never miss it. (Except for the one time I didn’t have it and saw a 65-year-old-freakshow at the bank that I couldn’t take a photo of. But anyway…)

Whenever I do constantly check it (and I do) I wonder what exactly I’m looking for. And I started playing Candy Crush on it recently and besides the fact that it’s a total timesuck, every single time I play I feel aggravated and unhappy and I hate it. In fact, I just uninstalled it from my phone. Just now.

Yay! Hunched over less, arms in the air more. I feel better already!

Thanks for chiming in, Charlene. I really DO think there’s something to it. For the simple reason that, as you said, when we stop all that manic checking for few hours, life seems to go better. Now, off to stand around like Wonder Woman!