I’m currently writing a novel. By currently writing a novel, I mean I have managed over the past year to squeeze out about eighty perfectly written, perfectly terrible pages. I was struck with the idea for the novel a month before “The Dark Knight” was released (to find out why this is relevant, you’ll have to read the novel, if there ever is a novel.) Not “The Dark Knight Rises” (2012) but “The Dark Knight” (2008).

During the years in which I have been currently writing the novel, which is to say not writing the novel, I’ve written several other books, two of my own, and one with another author. It’s not as if I can’t write; I just can’t write this novel.

I know exactly why I cannot write this novel. I cannot write this novel because it is going to be the best thing I’ve ever written, both profound and witty, but not so profound that it’s a huge depressing drag, nor so witty that it keeps readers at a distance. It’s going to be like no novel ever written, and even though most readers prefer to be only moderately challenged, and are drawn to familiar stories that feature off-beat detectives on the verge of retirement, or women who wear their hair in low ponytails and celebrate the bonds of female friendship in charming beach cottages, THIS novel, this novel that is unlike any novel every written, will nevertheless capture the imagination of every reader in the nation, thus propelling me to the top of the New York Times Bestseller list, while also winning every prestigious major award, while simultaneously Changing Lives (but not my own, too much.) It will be, above all, Important. It will be so Important that Jonathan Franzen will be wracked with guilt and, eager to make things right, fling himself at my feet, admitting it is me and not him, who is the Most Important Writer in America.

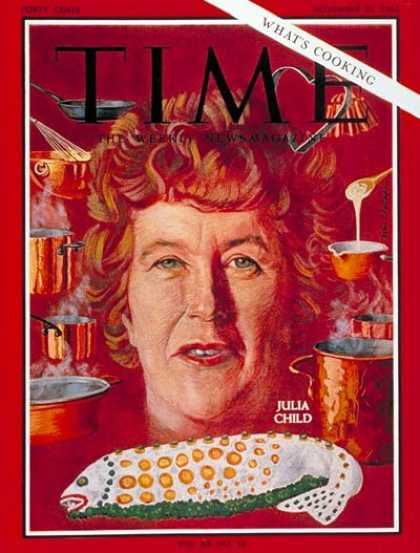

What am I doing on the cover of this magazine, when Karen Karbo and her genius unwritten novel are out there?

This place I find myself in the writing isn’t unfamiliar. As I tell my writing students, the only difference between them and me is that I understand my own process — which involves a few irrational months planning a future for the book so shiny and bright I become completely paralyzed. This always happens. Then, once the dreams for a book reach ridiculous levels (see above), my fever breaks, I snap out of it and throw myself into the maelstrom of making. The day I surrender my investment in the outcome is the day the writing really begins. E.M. Forster or D.H. Lawrence or one of those twentieth century British novelists with initials once said, “In every writer there is a peasant,” and I am never happier than when I’m grinding out the pages, peasant-like, dirt beneath my nails, figurative sweat streaming down the sides of my happy face.

By all reports Julia Child never had to go through any of this nonsense. She seems to have understood intuitively that happiness was to be found in the doing. When she agreed to do “The French Chef” on WGBH in 1963, she had no idea what she was getting herself into. She didn’t set out saying, “I’m going to help invent Public Broadcasting, snag an Emmy and be the precursor to the Food Network.” She and Paul didn’t even have a television, but a cooking show sounded interesting. Because the show was live, a 28-minute single take, she practiced her presentation at night in her Boston kitchen, with Paul directing, teaching herself how to move around the space, how to talk and cook and look into the camera. The day of taping they would arrive at the test kitchen before dawn with their own pans, bowls, utensils and ingredients. After it was over, Paul washed the dishes and often they would auction off the roasted chicken or French onion soup to recoup some of the expenses..

Julia was perhaps happier than most people because she worked harder than most people, even if there didn’t seem to be anything in it for her other than the joy of the task

Off to work on the novel. Jonathan, are you listening?

(Julia Child was also on the cover of Time Magazine, by the way.)

- “Our Lady of the Ladle.” With odd looking whole fish with yellow spots that looks like a refugee from Dr. Seuss.

sources: Jonathan Franzen/photographer Dan Winters/Time; Julia as The French Chef, www.ohio.com (1970 file photo); Julia Child/Boris Chaliapin/Time